Across the US, a handful of municipalities are radically reducing the amount of refuse they send to landfills, with the eventual goal of reaching “zero waste.” Seattle recycles or composts more than half of what its residents toss out. San Francisco diverts 77% of its waste from landfills. Even sprawling Los Angeles recycles or composts about two-thirds of its garbage.

hose numbers stand in stark contrast to the rest of the U.S., where the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates only about a third of waste is recycled or composted. The cities are getting the job done largely by having citizens and businesses sort trash more carefully, to recycle as much as possible.

Officials in these cities think they can go further. “It’s good; doesn’t mean we stop there,” says Tim Croll, solid-waste director for Seattle Public Utilities. “We know the word ‘low-hanging fruit’ is overused, but there is still more stuff to be gotten out of that waste stream.”

Less Than Zero?

The prime benefits in adopting zero waste are environmental; many cities that have enacted zero-waste plans say they have taken up the task in the name of sustainability. According to the EPA, recycling and composting are effective ways for households, communities and businesses to save energy while reducing water and air quality impacts as well as landfill-generated methane, a potent climate destabilizing greenhouse gas.

Zero Waste maximizes recycling, minimizes waste, reduces consumption and ensures that products are made to be reused, repaired or recycled back into nature or the marketplace. The Zero Waste International Alliancedefines it as such:

“Zero Waste is an ethical, efficient, economical, and visionary goal guiding lifestyle changes and practices emulating sustainable natural cycles, where all discarded materials are designed to become resources for others to use.Zero Waste means designing and managing products and processes to systematically avoid and eliminate the volume and toxicity of waste and materials, conserve and recover all resources, and not burn or bury them.Implementing Zero Waste will eliminate all discharges (90% reuse-recycle-diversion without incineration) to land, water or air that are a threat to planetary, human, animal or plant health.”

As well, supporters argue that reducing waste doesn’t necessarily mean increasing costs. For cities with limited landfill space—and the higher fees that come with it—most zero-waste activities cost less than normal garbage disposal, says Gary Liss, a zero-waste consultant who has helped about 20 cities form plans to reduce waste.

Why don’t cities shoot for 100% diversion? “We’re not crazy,” says Neil Seldman, president of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., that promotes sustainable communities. The closer cities get to that goal, the harder it is to go further, largely because there are so many products out there that just can’t be recycled—and people continue to buy them.

According to Paul Connett, “Waste is the evidence that we are doing something wrong. Our task is to fight over-consumption and its most visible manifestation: the throwaway ethic. Instead of trying to become more sophisticated about getting rid of waste, we have to stop buying things we do not need, and industries have to stop making things, which cannot be reused in some way.”

Extended Producers Responsibility (EPR) could make a difference on the production end, placing the legal, financial, and environmental responsibility for materials entering the waste stream with the manufacturer, not on the consumer or the local government at the end of the product’s or packaging’s life cycle. The end result is a fundamental shift in responsibility and financing so that manufacturers redesign products to reduce material consumption and facilitate reuse, recycling and recovery.

Cities can pass ordinances and require households and businesses to recycle and compost, but “they can’t control the behavior of residents,” says Chaz Miller, the state programs director for the National Solid Wastes Management Association, a Washington, D.C., trade group for the waste and recycling industry. “There is still a lot of material to dispose of in this country, and it’s going to remain that way for a long time,” he adds.

Indeed, despite increased recycling in recent years, Americans are still prodigious wasters. In 2009, the most recent year for which figures are available, Americans threw out roughly 243 million tons of trash—or about 4.34 pounds of garbage per person, per day, according to data from the EPA. After recycling, composting and incineration, about 132 million tons ended up in landfills that year.

Recycling by the Bay

One of the most comprehensive zero-waste strategies is San Francisco’s. The city has relied on ordinances and regulations to prod citizens and businesses into wasting less. In 2009, it became the first city in the U.S. to require food composting for residents and businesses, Rather than throw food scraps and dirty napkins into the trash, individuals and businesses must chuck their organic material into city-provided green bins.

Jepson Prairie Organics is one of two Recology-owned compost facilities that together process 600 tons of organics collected daily from the City of San Francisco - from BioCycle

The mandate led to a large boost in compost collection, says San Francisco Department of the Environment director Melanie Nutter. Recology, the city’s collection agency, now hauls more than 600 tons of organic waste to a composting facility each day. In an effort to “close the loop,” Recology sells the certified organic compost materials.

Along with putting compost in green bins, individuals and companies are expected to sort plastics, aluminum and papers into blue bins and garbage in black “landfill” bins. The less waste residents put in the landfill bin, the less they pay for curbside collection; recycling and compost collection are free. (The system, known as “pay as you throw,” is used in hundreds of other cities as well.)

San Francisco’s rules don’t end there. There’s also a mandate for waste at building sites. Construction and demolition crews must recycle or reuse at least 65% of the material from a site, which involves sorting all debris or ensuring it is hauled to a collection facility.

The result of all these efforts is a waste-diversion rate of 77%—the nation’s highest—and the city is aiming for 100% by 2020. Ms. Nutter says the city can reach 90% if it prods its citizens to be even more waste-conscious; about a third of the waste that San Francisco sends to the landfill is recyclable, and another third is compostable.

Officials in San Francisco say sustainability is the driving factor behind its push for zero waste. The city pays for garbage collection only from city buildings and property; residents and businesses pay for their service through fees. The city says residents pay about the same for curbside trash service as in nearby cities.

Shades of Green

Another zero-waste leader is Seattle, which diverts about 54% of its waste from the dump and hopes to reach 70% by 2022. The city mandates recycling for businesses and residents, and requires food composting for single-family residences.

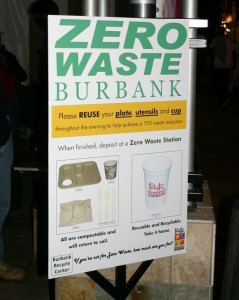

It has also banned the food-service industry from providing goods in plastic-foam containers, and requires single-use packaging—including plates, coffee cups and utensils—to be recyclable or compostable. Among the approved alternatives on the city’s website: drink cups made from corn, bowls made from tapioca starch and wooden utensils.

Still, not all high-achieving cities get there with mandates and bans. Los Angeles diverts over 65% of its waste from landfills and is shooting for 70% by 2013. But it doesn’t mandate recycling. “We don’t believe in banning, as a city,” says Alex Helou, assistant director of the city’s Bureau of Sanitation. However, the State of California, per AB341, will mandate for them and all municipalities. After July 1, 2012, a business that generates more than four cubic yards of commercial solid waste per week, or a multifamily residential dwelling of five units or more, shall arrange for recycling services consistent with state or local laws or requirements.

LA’s Mr. Helou says the bureau encourages residents by giving prizes like Starbucks gift cards to neighborhoods that increase their recycling the most. He says the city has also sought to make recycling as convenient as possible and has expanded the type of waste that consumers can throw into recycling bins to include items like plastic foam and milk cartons. Active movements in the city, however, are advocating for a stronger stance on recycling mandates.

Austin, Texas, currently recycles or composts about 38% of its waste and is in the process of finalizing its zero-waste plan. In addition to considering a recycling mandate, the city has pursued an original outreach campaign. Earlier this year, “Dare To Go Zero” premiered on the city’s public-access channel. The “Biggest Loser”-style reality show challenged four families to reduce their waste by 90% over the course of five weeks.

The city’s director of solid-waste services, Bob Gedert, says Austin hopes to ratchet up its diversion rate to 75% by 2020 through a mix of regulation and outreach, but says the city does not expect to reach zero waste until 2040.

Innovate Instead of Incinerate

Officials in San Francisco, like many other zero-waste supporters, maintain that incinerating waste increases greenhouse-gas emissions, and note that incineration destroys, rather than conserves, resources.

Still, many city officials agree that some sort of technological help will be needed as they get closer to zero waste. Seattle’s Mr. Croll says he is interested in anaerobic digestion, a process where micro-organisms break down organic waste and produce methane, which can later be used for energy. San Francisco is hoping to rely on advanced mechanized sorting systems that pick more recyclables from the garbage flow, Ms. Nutter says.

After that, she says, it may be out of the city’s hands. “There are some items in the waste stream that can’t be recycled or reused or repurposed,” she says. “So, in that case, we think the last 10% will really come down to working with manufacturers” to reduce and rework materials packaging.

Mr. Liss, the zero-waste consultant, says that at some point cities have to say, “We’ve done a lot with recycling, but we need to do a lot more with reducing and reusing.”

No comments:

Post a Comment